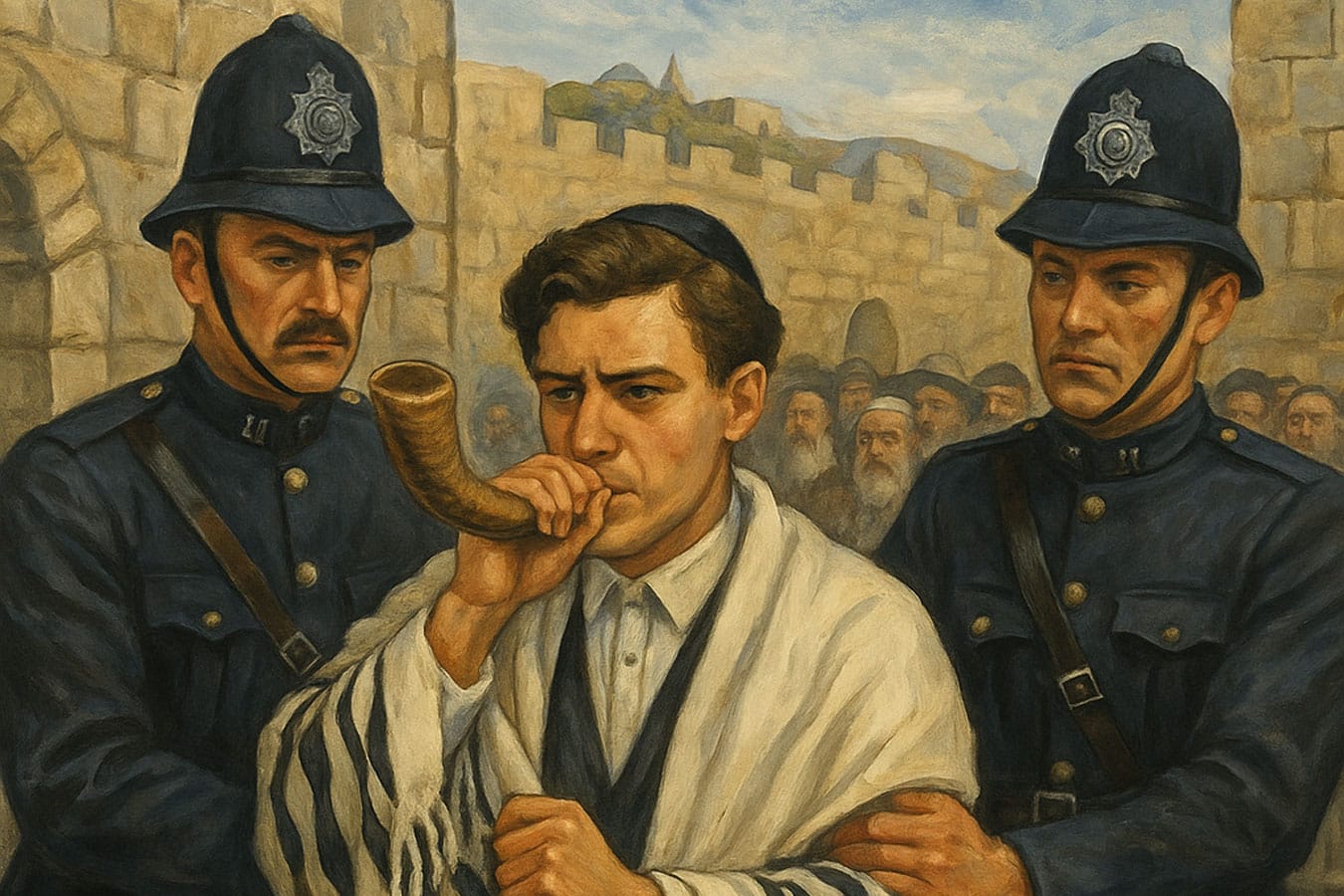

The story of Moshe (Moshe-Tzvi) Segal is the trajectory from Poltava to Jerusalem. Youth in the Ukrainian Jewish environment, strict study routine, and the first Zionist circles turn into a public gesture of freedom at the Western Wall on Yom Kippur in 1930. He gave the final sound of the shofar — tekiah gedolah — and was arrested by the British police; that same evening, Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook secured his release. This frame marks the beginning of the long journey of a man who not only protested but also built institutions of Jewish life.

Birth and Childhood in Poltava (1904–1924)

Moshe Segal was born in Poltava on February 23, 1904 (6 Shvat 5664) to the family of Avraham-Mordechai ha-Levi Segal and Henna-Leah Minkin. His home was traditionally Jewish, with deep religious and Zionist traditions.

From an early age, he was distinguished by his eagerness for books. Segal’s “second school” was not a gymnasium but the Poltava Jewish Community Library, where he spent hours reading philosophical treatises, chronicles, and journalism. There he first became acquainted with the works of medieval thinkers, while simultaneously getting involved in Poltava’s Jewish youth organizations: already in 1916 he joined “Tikvat Yisrael,” and from 1920 he actively participated in “Tzeirei Zion” and “Hechalutz.” These unions combined learning with practice and instilled in teenagers the aspiration for aliyah — relocation to Eretz Yisrael.

During World War I, the Mir Yeshiva was evacuated to the city for several years (1914–1921), and Moshe studied at the Mir Yeshiva in Poltava from about the age of ten to fifteen. This accustomed him to the discipline of the beit midrash and the “bundle” of three words: Torah, Eretz Yisrael, action.

By the early 1920s, Moshe Segal had ceased to be just a curious teenager. He became one of those who connected the “reading” youth with the “practitioners”: he participated in organizing hachsharot — agricultural internships to prepare for relocation to Eretz Yisrael. These camps helped teenagers and young people not only physically prepare for future life but also feel the unity of the cause. Moshe supervised the dispatch of young people to farms in southern Ukraine, ensuring that the community in Poltava was not only a center for studying books but also a launching pad for action.

These twenty years in Poltava shaped him as a “man of action.” It was there that book learning, public work, and the first leadership qualities merged, which he carried throughout his life — from the arrest at the Western Wall to participation in underground organizations and the establishment of Israel.

Reference: What is the “Mir Yeshiva” and what does it have to do with Poltava

The “Mir Yeshiva” is one of the most influential Lithuanian (Ashkenazi) Torah academies. Founded in the town of Mir (now Belarus) in 1815–1817 by the Tiktin family (Rabbis Shmuel, Avraham, and Chaim-Leib Tiktin), it became the flagship of the “Volozhin” school with an emphasis on deep Talmudic study and strict academic discipline. At the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, it was strengthened by Rabbi Eliyahu-Baruch Kamai and his son-in-law, the future Rosh Yeshiva Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel; the spiritual “engine” of the interwar period was the mashgiach Rabbi Yerucham Levovitz — under him, Mir was called “the yeshiva where future heads of yeshivas are raised.”

The key to our topic is the Poltava period. With the start of World War I, in 1914, the yeshiva was evacuated from Mir to Poltava, where it operated until 1921. It was during these years that Moshe Segal studied at “Mir” in Poltava: the beit midrash, the rhythm of study, partner responsibility, and the “bundle” of three words — Torah, Eretz Yisrael, and action — were formed in him not in an abstract “Lithuanian” environment but in the specific Ukrainian Poltava.

After the Poltava period, the Mir Yeshiva had a rather dramatic fate:

- 1921 — after the Civil War and Soviet power in Ukraine, it became impossible to maintain a religious educational institution. The yeshiva left Poltava and returned to the town of Mir (then Poland).

- 1939 — after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the division of Poland, part of Belarus went to the USSR. The yeshiva found itself under Soviet rule, making its existence impossible.

- 1940–1941 — the leaders and students of the yeshiva moved to Lithuania. From there, thanks to the help of Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara and Dutch diplomat Jan Zwartendijk, several hundred students received transit visas.

- 1941–1947 — refugees from the yeshiva ended up in Shanghai (China), which was then under Japanese occupation. There, the yeshiva continued to function, which is considered a unique case of preserving a traditional Talmudic school during the Holocaust years.

During World War II, “Mir” experienced a unique escape “via the eastern route”: Mir → Vilna/Keidan (Lithuania) → transit visas → Kobe (Japan, 1941) → Shanghai (1941–1947).

After the war, two main centers grew from this line: in Jerusalem (officially established in 1944–1945, Beit Yisrael district) and in Brooklyn (Mirrer Yeshiva, established in the 1950s under the leadership of Rabbi Avraham Kalmanowitz). The Jerusalem branch was successively headed by Rabbi Chaim Shmulevitz, Rabbi Nachum Partzovitz, Rabbi Binyamin Beinush Finkel, Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel; today it is led by Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel along with other senior roshei yeshiva (including Rabbi Yitzchok Ezrachi).

Where and how many students now. The Jerusalem “Mir” is the largest yeshiva in the world: according to open data, it has about over nine thousand students (≈9–9.6 thousand). The American Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn has several hundred students (school branch and post-school program), which is significantly smaller but historically key to preserving tradition in the USA.

The conclusion for our material is simple: “Mir” is the “Oxford” of the Torah world; Poltava was its temporary home in 1914–1921; Segal is one of those whom the “Poltava Mir” shaped. Therefore, in his biography, we highlight both the yeshiva itself and its connection with Poltava in such detail.

Poltava: Ukrainian and Jewish History to the Present Day

Middle Ages. The first mention of Poltava dates back to 1174. At that time, it was a fortified settlement on the Vorskla River, part of the Principality of Pereyaslav.

Tatar-Mongol Invasion. In the 13th century, Poltava, like other cities of Kievan Rus, suffered from Batu’s campaigns (1237–1240). The city was destroyed, the population partially exterminated or taken captive. For several centuries, the territory was under the influence of the Golden Horde.

Polish-Lithuanian Period. From the 14th century, Poltava was under the rule of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and then the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During this period, the first Jewish families and traders appeared.

Cossack Era. In the 17th century, Poltava became the center of a Cossack regiment. During Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s uprising (1648–1657), the city played a significant role in the struggle for autonomy.

Battle of Poltava. In 1709, the decisive battle of the Great Northern War took place here: the alliance of Charles XII and Ivan Mazepa was defeated by Peter I. After this, Poltava was secured for the Moscow state.

Second Half of the 18th Century. By this time, a Jewish community already existed in Poltava, although Jews were formally restricted from living in central areas of Ukraine. Despite this, the first synagogues, charitable funds, and schools were formed here.

19th Century. In 1802, Poltava received the status of a provincial center. The city became the cultural capital of Left-Bank Ukraine: Ivan Kotlyarevsky worked here, Nikolai Gogol began his studies, and theaters opened. By this time, the Jewish community had reached significant influence: according to the 1897 census, 11,046 Jews (20.5% of the population) lived in Poltava. There were 10 synagogues, a Talmud Torah with 300 students, a women’s school, a library (8,000 books), and a Jewish hospital.

World War I and Interwar Period. From 1914–1921, the famous Mir Yeshiva evacuated from Belarus was located in Poltava — one of the largest centers for Torah study. During this time, future activist Moshe Segal studied here. In 1926, about 93,000 Jews lived in the province, and in the city itself — 18,476 (20.1% of the population). But by 1939, the share had decreased to 9.9%.

World War II. The Germans entered Poltava on September 18, 1941. Already on September 25, about 5,000 Jews were shot, and on November 23 — another 3,000. In total, during the occupation, more than 22,000 Jews died in the region.

Soviet Period. After the war, the community partially recovered, but under atheistic policies. In 1959, the authorities closed the last functioning synagogue, and Jewish life went underground. Meanwhile, the city developed as an industrial and educational center of the Ukrainian SSR.

Independent Ukraine. Since the late 1980s, the community began to revive. In the 1990s, a Chabad center, the “Or Avner” school, and the “Hesed Nefesh” program appeared in Poltava. According to the 2001 census, about 1,800 Jews (0.3% of the population) lived in the city.

Russian Aggression (2022–2025). Poltava was again under attack.

- April 2, 2022 — first rocket attacks on infrastructure.

- September 3, 2024 — rockets hit the Military Institute of Communications and a hospital: dozens killed, hundreds injured.

- February 2, 2025 — a rocket destroyed a residential five-story building, killing 14 people, including children.

- March 28, 2025 — mass attack by “shaheds” on industrial zones.

- July 3, 2025 — drones hit the military enlistment office and neighboring houses.

Today. Despite the threats, Poltava remains part of independent Ukraine — the administrative center of the Poltava region and an important industrial and cultural hub of Central Ukraine. According to various data, about 280–320 thousand people live in the city, and together with the surrounding villages in the urban community — up to 600–650 thousand. The Jewish community, though small, is active: the synagogue, Chabad center, “Or Avner” school, social projects, and memorial initiatives remind of the past and help shape the future.

Jews of Poltava: Notable Figures

The history of the Jewish community of Poltava is reflected in the biographies of its outstanding natives and residents. These names are known far beyond Ukraine, and their contributions have become part of world Jewish history.

- Yitzhok Yitzhak Krasilshchikov — a rabbi nicknamed “The Gaon of Poltava.” He was the author of a fundamental commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud and is considered one of the key figures in its study in the 20th century.

- Elias Tcherikover — born and raised in Poltava. Historian, one of the founders of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Vilna. His works are dedicated to the history of Jewish life and pogroms in Eastern Europe.

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi — a native of Poltava, the second president of the State of Israel. In Poltava, he received a Jewish education, participated in the Zionist movement, and in Israel became one of the central state figures.

- Alina Treiger — born in Poltava, became the first female rabbi ordained in Germany after World War II. Her activities became a symbol of a new stage in the development of Judaism in Europe.

- Jacob (Yasha) Gegna — a klezmer musician from Poltava, a famous violinist and teacher. His name is associated with the development of Jewish musical tradition in the early 20th century.

- Pavel Gertsyk — a Poltava colonel during the time of Ivan Mazepa. He came from a Jewish family that moved to Poltava. His family occupied a prominent place in the Cossack and Ukrainian elite of the 18th century.

The Move of Moshe Segal to Palestine and the Path to the Kotel

In 1924, Moshe repatriated to Palestine with his parents.

In Palestine, Segal worked as a stonemason, studied at “Merkaz ha-Rav”, and got involved in “Beitar”.

Summer-Fall 1929 — defense of Tel Aviv during the Arab riots; at the Kotel, he participated in demonstrations and organizational work. In the fall of 1930, he was detained for several days for participating in a protest against the visit to Palestine of the British Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies Dr. Drummond Shiels; a few days later, all detainees were released by order of the High Commissioner.

Episode at the Kotel (1930): How It Happened

After the riots of 1929, police restrictions of the mandate administration were in effect at the Western Wall: it was forbidden to bring “demonstrative religious items” and blow the shofar; the police enforced this already in 1930 (the law would come later).

Yom Kippur 5691 fell on the evening of October 1 → evening of October 2, 1930 (not “September 21” — this date is mistakenly mentioned in several materials).

Segal took a shofar in advance from Rabbi Yitzhak Avigdor Orenstein (the first official “rabbi of the Wall”) and hid it under his tallit. At the end of Ne’ilah, he gave a long final sound tekiah gedolah, as is customary to conclude the fast; the police detained him on the spot and took him to the Kishle station.

The Chief Rabbi of Eretz Yisrael Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook called the administration and stated that he would not conclude the fast until Segal was released; closer to midnight, Moshe was free.

Segal did this as a religious-political gesture: to conclude Yom Kippur with the prescribed tekiah gedolah at the holy site and remind that this place is a sanctuary of the Jewish people.

He consciously concluded Yom Kippur with a tekiah gedolah at the Kotel, openly challenging British prohibitions and asserting the right of Jews to pray according to their custom. The gesture worked as mobilization: after his arrest and Rabbi Kook’s intervention, the shofar sounded there annually until 1948, turning into a ritual of nonviolent disobedience.

In the following years until 1948, at Segal’s initiative, young people annually smuggled a shofar to the Kotel and gave a tekiah gedolah — despite arrests and fines.

What Was This Law and Where Is the “Logic” of the Dates

The International Commission on the Western Wall (Chairman — Eliel Löfgren, members — Charles Barde, Johann van Kempen) completed its work in December 1930. The commission recognized the Muslim waqf‘s ownership of the wall and the plaza, and for Jews — the right of “free access for prayer” with reservations: a ban on the shofar and a list of what can/cannot be brought to the wall.

These findings were turned into law in the Palestine (Western or Wailing Wall) Order in Council, 1931, which came into force on June 8, 1931; for violation — fine of 50 pounds or imprisonment up to 6 months. Consequently, in 1930, Segal was detained under existing police instructions, and in 1931, the same regime was codified.

After the “Sound”: Not Only Protest but Also Construction

Segal remains a man of long distance.

In the 1930s and 1940s, he went through right-wing national movements (Etzel/Irgun from 1931, contacts with “Lehi” from 1943; in parallel — Brit ha-Biryonim 1931–1932, Brit ha-Hashmonaim from 1937) — this is evident from his organizational “trail.” After the declaration of the state, he moved into community routine: in the 1950s, he participated in the establishment of Kfar Chabad (the settlement was founded in 1949), worked in agriculture and the secretariat.

After June 1967 (Six-Day War), Segal returned to the Old City and contributed to the revival of the “Tzemach Tzedek” synagogue and regular minyan; in the 1970s, he participated in religious and public initiatives to strengthen presence at holy sites (including movements like “El Har ha-Shem”/“El Har ha-Bayit”).

Recognition and Memory

In 1974, he was awarded the title of “Yakir Yerushalayim” (Honored Citizen of Jerusalem). This is one of the highest municipal awards given to people who have made a significant contribution to the development of the city.

In his memory, a square near Mount Zion in Jerusalem is named after him. This fact emphasizes that his name and act — blowing the shofar at the Western Wall — are entrenched not only in historical memory but also in the urban toponymy of Israel’s capital.

He died on Yom Kippur, September 25, 1985 (10 Tishrei 5746), and is buried on the Mount of Olives.

Final Note

For our section “Jews from Ukraine“, this is almost a textbook example.

Poltava is not just a line in a questionnaire, but a school of character: the library and circles, study at the Mir Yeshiva specifically in Poltava, experience of self-organization and hachshara. Jerusalem is the continuation of the same line: where formal rules humiliate the meaning of prayer, he blows; where the noise subsides, he builds — a settlement, a synagogue, community institutions.

And yes, if someone looks up “September 21, 1930” in the wiki — we will point to October 1–2, 1930 as the real dates of Yom Kippur 5691 and that the ban was initially police, and on June 8, 1931 it became law. This removes all “logical” nitpicks.