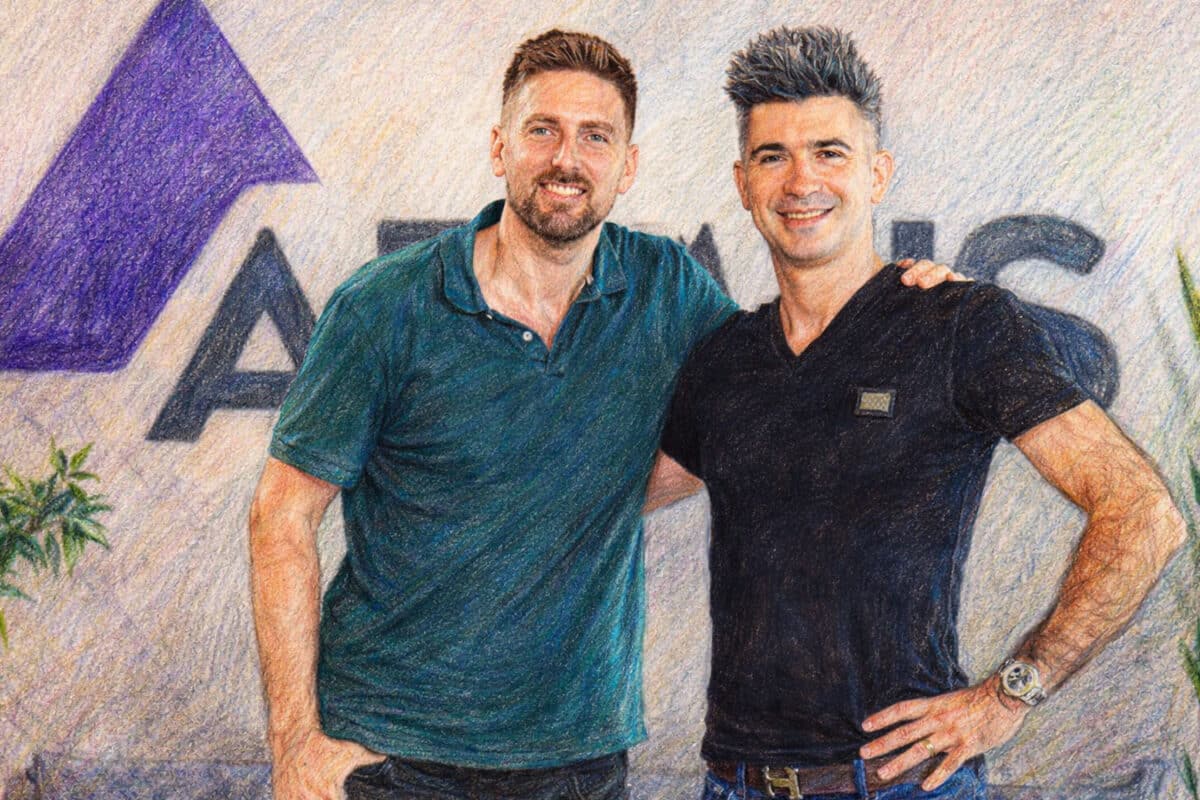

American corporation ServiceNow announced the acquisition of the Israeli cybersecurity company Armis for $7.75 billion. The parties announced the closing of the deal on December 23. Armis was founded by two Israelis — Eugene Dibrov and Nadir Izrael, reported the Israeli portal “Vesti” on December 23, 2025.

According to industry sources, the final amount may exceed $8 billion, taking into account bonuses for employee retention. In this form, it is one of the largest exits in the history of Israeli high-tech and, as noted, the fourth largest.

What exactly ServiceNow is buying

ServiceNow explains the deal by stating that the acquisition of Armis should expand their security and risk management solutions and accelerate the strategy of “proactive autonomous cybersecurity.”

Simply put, it’s about a platform that helps organizations see what is actually connected to their network, where the weak spots are, and how to quickly respond to incidents — not just at specific points, but across the entire infrastructure.

What Armis does and why it’s expensive

Armis specializes in protecting devices and equipment that are connected to networks in real-time: printers, cameras, corporate “hardware,” IT infrastructure elements, as well as operational technologies — what works “inside” industries and services.

The approach is based on understanding the normal behavior of devices. The system tracks typical scenarios, detects anomalies, and, if necessary, can help isolate a device from the network to stop the development of an attack.

A separate focus is on areas where there is a lot of connected equipment and the cost of failure is particularly high: healthcare (monitors, diagnostic devices) and industry (production lines). It is there that cyber risks often turn not into a “leak,” but into a halt in processes.

Why the amount could grow to 8+ billion

The company was founded in 2016. In November last year, Armis completed a funding round of $435 million, after which the valuation reached $6.1 billion.

The difference between the “purchase price” and the “possible outcome” includes money for retaining key employees and teams. For the cybersecurity market, this is standard logic: the product is bought, but in reality, they buy people who can quickly develop the product and maintain the pace.

The Ukrainian trace in the deal’s history

The connection of Armis with Ukraine is not through offices or sales, but through the biography of one of the founders. Eugene Dibrov repatriated from Dnipro at the age of four. He moved to Israel with his mother, grandfather, and grandmother and settled in Rehovot.

This context is important for Israeli society: the story of repatriation here often becomes part of a professional trajectory — especially in the technology sector, where the “social elevator” really works but requires very tough adaptation.

The founder’s story: the path from Dnipro to Israeli high-tech

For the audience in Israel and those from Ukraine, there is a separate, human layer in this story — the biography of co-founder Eugene Dibrov.

In an interview in 2022, he said that he repatriated from Dnipro at the age of four. Together with his mother, grandfather, and grandmother, the family moved to Israel and settled in Rehovot.

According to him, his parents divorced before repatriation. He did not maintain ties with his father, and his grandfather and grandmother took on a key role in his upbringing. They did everything so that the boy did not feel “worse than others,” even when life in the new country started from scratch and without discounts for past professions.

Before moving, his grandfather worked as an engineer and manager in a gas company. In Israel, he got a job at Pazgaz — and on the first day, he heard that his work would not be managerial: he needed to load gas cylinders. His grandmother, who previously managed a pharmacy, and his mother — an economist with a higher education — also took on several jobs simultaneously. The family recalled the hard work of picking oranges as part of this period when survival and adaptation went hand in hand, without pause.

At some point, the family made a tough but clear decision: they would most likely not return to their previous professions, so the bet was on the child’s future. Dibrov said that they always found money for books and clubs — technological, mathematical, sports. His grandfather brought suitcases of books from their Ukrainian apartment, and his mother deliberately bought him new books — as if it were an investment that could not be postponed.

He also recalled a childhood dream of a car — even in elementary school, he saw that other children had one, but his family did not. Later, he said a phrase that repatriates can easily understand: “Today I have an SUV, but it is much more important for me to help my parents.” After many years of living in rented apartments, he helped his family get a mortgage and planned to buy them a more spacious apartment in Rehovot.

However, success, according to him, was overshadowed by loss: his grandmother passed away shortly before the previous major deal when the company was sold for $1.1 billion. But there is also a very Israeli scene in the story — neighbors hung congratulatory posters, and his mother’s friends called her with excitement and joy, as if it were the victory of not just one family, but the whole neighborhood.

Separately, Dibrov also talked about his service in Unit 81 of the IDF Intelligence Corps — for many Israeli technological careers, this is not just a “line,” but an environment where skills and connections are formed, which later turn into a product and company.

What’s next: the effect for Israel and the diaspora

The deal around Armis is simultaneously about big money and a very specific trajectory of a repatriate from Ukraine: from kindergarten language to a company bought for billions.

For Israel, it is another argument that high-tech remains a pillar of the economy and export strength even in difficult years. For the repatriate community, it is a reminder that stories of integration and success do not always look smooth: often it is the hard work of a family, lost professions, several jobs at once, and a stubborn bet on the child’s education.

And it is precisely such stories — without advertising gloss and unnecessary “references” — that most often explain why Israel continues to be a place where technology companies grow to deals of global scale. NAnews — News of Israel | Nikk.Agency