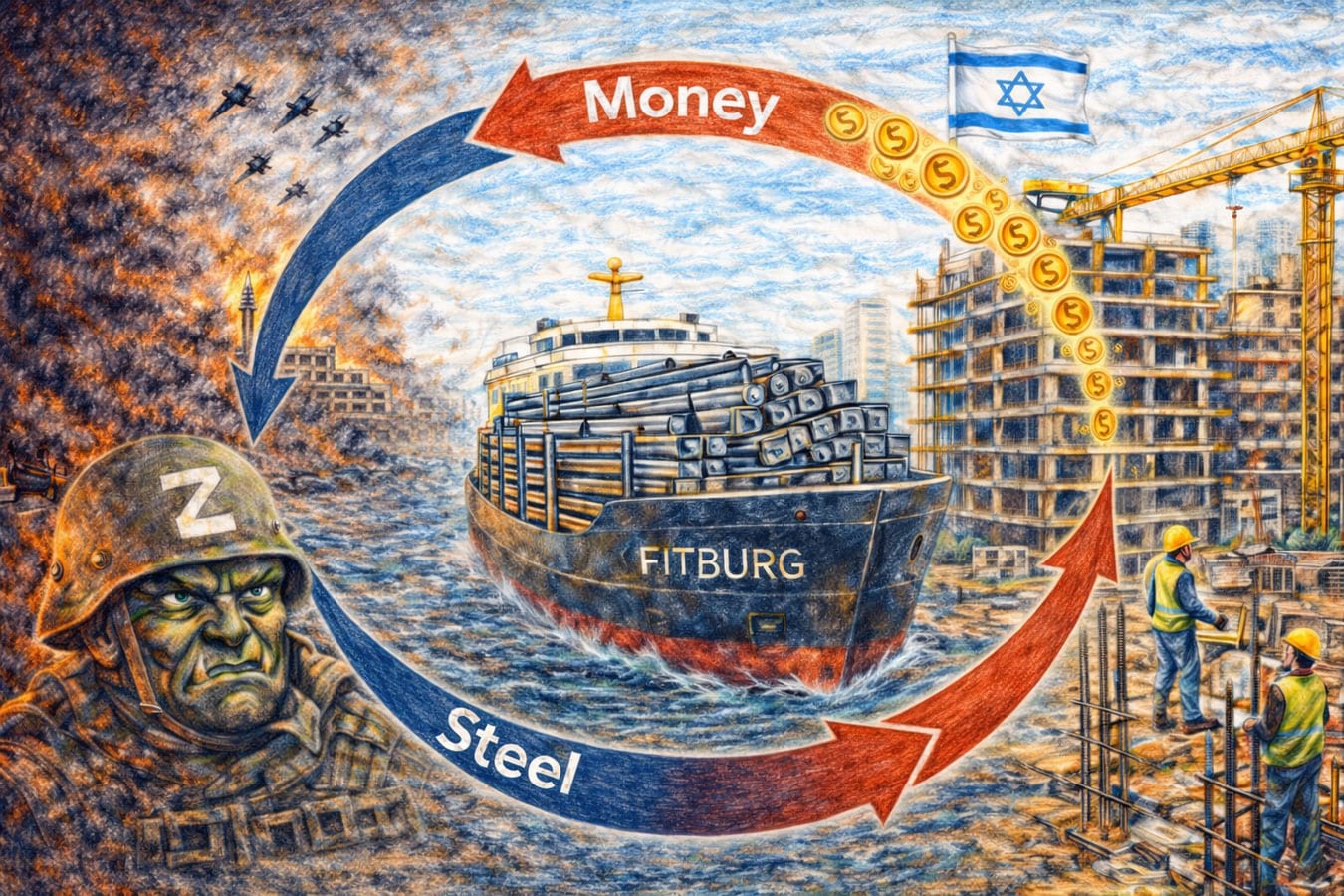

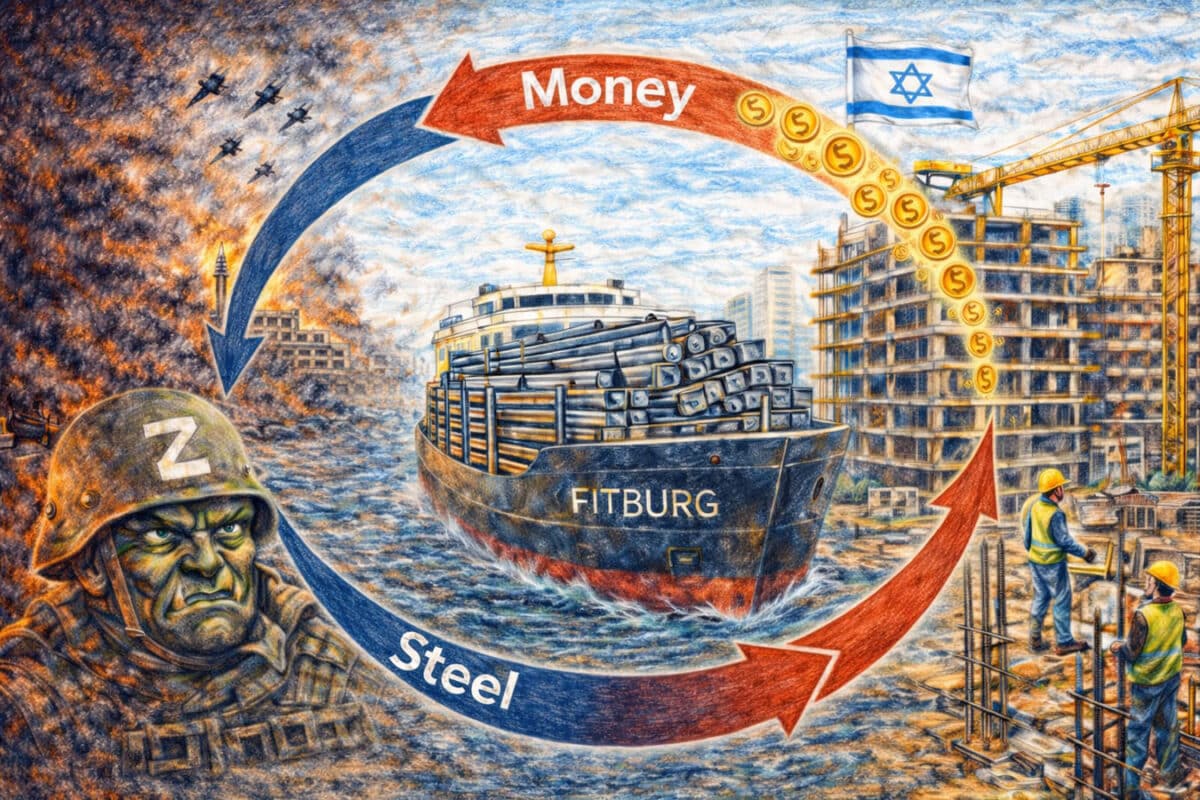

Uncomfortable thesis – “Every major export shipment is a contribution to Russia’s ability to continue the war”.

The story began on January 7, 2026, with a short message from Finland. Customs and port authorities allowed a vessel carrying sanctioned steel of Russian origin to Israel to continue its journey. An inspection was conducted, the cargo was recognized as falling under EU sanctions, but no criminal proceedings were initiated: the vessel entered Finnish waters not on its own initiative, but at the request of the authorities.

Formally — a standard procedure.

In fact — a public signal that the sanctions economy is not as airtight as commonly believed.

And most importantly — this signal directly concerns Israel.

Why this particular shipment became a “problem”

After February 24, 2022, when Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, sanctions became a key tool of pressure. Already in March–April 2022, the European Union approved the first packages of restrictions, and by the end of 2022, they had turned into a systemic regime.

By 2024–2025, the EU had introduced:

— a complete ban on the import of Russian steel and semi-finished products;

— restrictions on shipping and insurance;

— blocking of dozens of banks;

— freezing of assets of more than 2,000 individuals and legal entities.

Simultaneously, similar measures were introduced by the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, Australia, South Korea, and New Zealand.

The reason why metallurgy was separately sanctioned is simple and recorded in the EU explanatory notes:

steel is one of the key export items directly filling Russia’s budget.

According to the European Commission, before the war, Russia exported metal products worth 40–45 billion dollars a year. After the imposition of sanctions, volumes decreased, but exports did not disappear — they were redirected to markets outside the EU.

Israel turned out to be one of these markets.

Where exactly in Israel this steel is used

It is important to note: it is not only about housing.

Russian steel is used in:

— railway projects and new lines;

— bridges, interchanges, and tunnels;

— industrial and logistics zones;

— ports and terminals;

— municipal projects — schools, hospitals, shelters;

— engineering and dual-use defense facilities.

According to Israeli industry associations, up to 60% of all steel consumption is not for housing, but for infrastructure and government orders. Savings on metal affect not just one market, but the entire system of budget expenditures.

What really makes up the cost of construction

The thesis often heard is: “without cheap steel, housing will become unaffordable“.

Facts show a different picture.

The average cost structure of construction in Israel looks like this:

Materials — 45–55%, of which:

— steel and metal structures — 8–12%;

— concrete and cement — 15–20%;

— finishing — 8–12%;

— engineering systems — 7–10%.

Labor — 20–25%.

Land, permits, and regulation — 15–25% (especially in the center of the country).

Financing, interest, insurance, and risks — 10–15%.

Even with a 25–30% increase in steel prices, the direct effect on housing costs is 2.5–3%, and considering indirect factors — up to 5–7%.

This is significant.

But it is not a systemic collapse.

Are there real alternatives to Russian steel

Alternatives to Russian steel exist. The question is that each of them requires either a higher price, more complex logistics, or stricter standards and long-term contracts. If Israel wanted to reduce or stop purchasing Russian steel, it has several replacement directions — none perfect, but all realistic.

The first scenario is expanding purchases in European Union countries: Germany, Italy, Spain, as well as several Eastern European producers. European steel fits well into transparent government procurement, is easier in terms of compliance, and does not carry sanction risks. The main downside is obvious: according to industry estimates, such steel can be about 40–60 percent more expensive than Russian. The second downside is contractual inertia: European factories often work on long contracts and are less flexible for urgent infrastructure needs.

The second scenario is increasing the share of Asian supplies, primarily from India. This can provide large volumes and potentially a softer price than Europe, but more expensive than Russian. In practice, it will be necessary to consider long sea logistics, the need for additional certification, and adaptation to Israeli standards. As a result, part of the “savings” is often eaten up by delivery times and associated costs, especially if it is about large projects where delays are more expensive than the metal itself.

The third option is using Chinese metal products in certain categories where requirements for exact characteristics and certification are simpler. This is technically possible, but the market is cautious about this scenario: quality is uneven, certification can be lengthy, and political and trade risks increase the price of uncertainty. For government and infrastructure projects, this is usually critical.

A separate scenario is Ukraine as a strategically and morally significant alternative. Before 2022, Ukrainian metallurgy was a notable supplier to the region. Theoretically, Israel could support Ukrainian supplies and fix them as a priority, but in the short term, there are limitations: war, damage to enterprises, logistics difficulties, and irregular volumes. This direction is realistic as part of a combination, but not as the only replacement.

And only after listing systemic alternatives should Turkey be mentioned — with an important caveat. Previously, Turkey was one of the largest sources of construction steel for Israel: in some years, Turkish products accounted for up to 25–35 percent of rebar and other long steel imports, meaning hundreds of millions of dollars a year. However, after 2024, this channel became politically and logistically unstable due to trade restrictions. Even before these restrictions, Turkish steel was on average 20–30 percent more expensive than Russian, and today it is difficult to consider it as a “basic” replacement.

Thus, the alternative to Russian steel is not one supplier, but a combination of sources: part from the EU (compliance and quality), part from India (volumes), targeted purchases from China (where permissible), and Ukraine as a strategic direction that can be supported by contracts. The price will almost inevitably rise, but it will no longer be a question of “is there a choice”, but a question of “what choice model is Israel ready to accept”.

Thus, refusing Russian steel does not mean the absence of choice. It means transitioning to a combination of more expensive, more complex, but politically and reputationally safe sources, just as the EU, the US, and all other democracies in the world have already done.

How payments are made despite sanctions

Sanctions on Russia’s banking system are strict, but not absolute. Not all banks are disconnected from international transactions, and EU and US regimes differ.

In practice, the following are used:

— intermediaries in third countries;

— alternative currencies;

— multi-step payment chains;

— trading structures formally not under sanctions.

Legally, such schemes are permissible. Economically — they mean one thing: money reaches the Russian producer, and then — into the budget.

Who supported the sanctions — and who stayed aside

The entire democratic West supported the sanctions.

They were not joined by Iran, Venezuela, Syria … China, India, Brazil, Turkey, and most Asian and African countries.

But among developed liberal democracies, the situation is different.

Israel – the only democracy outside the sanctions consensus

Israel remains the only developed liberal democracy, closely connected with the US and the West, which has not officially joined the sanctions against Russia.

This means that trade, including steel imports, remains legal.

But it also means that part of Russia’s foreign exchange earnings continues to be formed through such supplies.

Since 2022, Russia has earned hundreds of billions of dollars from exports. Metallurgy brings in tens of billions of dollars annually — money that goes into the budget, from which the war against Ukraine and Moscow’s cooperation with Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas are financed.

The price per square meter and the price of position

Refusing Russian steel would not stop construction in Israel. It would make it more expensive — by a few percent.

But the question is no longer in accounting.

Saving on the cost of housing and infrastructure through trade with an aggressor state is a political and moral choice. It cannot be hidden behind the formula “everything is legal”.

This choice is now at the center of public discussion.

How Europe and the US manage without “cheap” Russian steel — and why for democracies the moral choice turned out to be more important than the price

After 2022, the countries of the European Union and the United States faced the same choice as Israel. Russian steel was cheap, familiar, and technologically understandable. Refusing it meant an increase in construction costs, pressure on infrastructure budgets, and business dissatisfaction.

Nevertheless, the EU and the US consciously took this step.

In Europe, the import of Russian steel was banned gradually, starting in the spring of 2022. To compensate for the deficit, three mechanisms were used.

- First — redistribution of domestic production: European steel plants received state support, energy subsidies, and guaranteed orders.

- Second — diversification of imports: South Korea, Japan, partially India.

- Third — temporary acceptance of a higher price as a politically justified cost factor.

In the US, the situation was similar. Washington already had a developed domestic metallurgy, but still faced rising prices for infrastructure projects. The response was systemic: federal programs, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, directly included higher material costs as an acceptable price for a strategic and moral position. Official explanations for the programs emphasized: savings achieved through trade with an aggressor are considered unacceptable.

It is important to note: neither the EU nor the US claimed that refusing Russian steel “costs nothing”. It cost money. But this increase in expenses was recognized as part of the responsibility of democracies, not a mistake.

Here lies the key line of distinction. For Western democracies, sanctions were viewed not only as a tool of pressure but also as public confirmation of values. Economic losses were deemed acceptable because the alternative would be complicity — direct or indirect — in financing the war.

What Israel could do in this logic

Israel is not in a unique economic trap. Alternatives exist, and the market is already familiar with them. It is not about a sharp break, but about a political decision.

Israel could:

— announce a phased refusal of Russian steel with a transition period;

— fix the priority of supplies from the EU, India, Ukraine, other alternative suppliers;

— incorporate the increase in infrastructure project costs as a conscious state position;

— introduce transparency in government procurement, where the origin of metal becomes a public parameter;

— synchronize key restrictions with partners in the EU and the US without a formal “full package of sanctions”.

None of these steps would mean an immediate economic crisis. They would mean recognizing that for a democratic state, the origin of money and materials matters.

This is exactly how Europe, the US, and all other democracies in the world acted: not because it was cheap, but because it was considered right.

This is where the divergence of approaches lies: the price of steel is indeed measured in percentages. But the price of moral choice is in trust, political weight, and the ability to explain to allies why “everything is legal” turned out to be more important than the common pressure on the aggressor.

For Israel, this discussion is not about slogans, but about standards: what the state considers an acceptable source of savings in wartime conditions when Russia simultaneously works with Iran and its proxies. And that is why the question of the origin of steel turns into a question of position. NAnews — News of Israel | Nikk.Agency